Understanding the Evolution of Sweeteners

Traditional sweeteners such as sugar and high fructose corn syrup represent the first wave of industrial sweetening agents. These substances are affordable and easy to produce in large volumes, yet they deliver nothing but empty calories. Their consumption has been strongly associated with serious health concerns, including excessive weight gain, the development of type 2 diabetes, dental decay through cavities, and the onset of metabolic syndrome. Moving to the next phase, artificial sweeteners like NutraSweet, Splenda, and Sweet’N Low emerged as second-generation options. These provide virtually no calories, making them appealing for calorie-conscious individuals. Nevertheless, various studies have highlighted potential risks and cautions regarding their long-term use and possible adverse health impacts.

The third category includes sugar alcohols, such as sorbitol, xylitol, and erythritol. These third-generation sweeteners offer a reduced calorie profile compared to regular sugar, which sounds promising at first glance. However, they often come with unwanted side effects, particularly gastrointestinal discomfort like laxative actions, and in some cases, even more troubling health implications that warrant careful consideration.

Discovering Allulose: A Rare Natural Sugar

Allulose stands out as a natural monosaccharide classified among the so-called rare sugars due to its scarcity in the natural world. It occurs in very small amounts in certain foods like figs, raisins, and wheat, but not in quantities sufficient for commercial use until recently. Thanks to modern biotechnological innovations, including enzymatic processes involving genetically modified microorganisms, producers can now manufacture allulose on a larger scale. This breakthrough has made it feasible to incorporate this once-elusive sugar into everyday products as a viable sweetening alternative.

Exploring Allulose’s Potential for Fat Reduction

Researchers conducted a comprehensive trial to assess how allulose influences fat mass in humans. Over a hundred participants were divided into groups receiving either a placebo—consisting of a tiny 0.012 grams of sucralose administered twice daily—or varying doses of allulose: one teaspoon (4 grams) twice a day, or one and three-quarters teaspoons (7 grams) twice a day. This regimen continued for a full 12 weeks. Importantly, none of the groups altered their daily physical activity levels or total caloric intake. The results were striking: those supplementing with allulose experienced notable reductions in body fat percentages. On the flip side, measurements of LDL cholesterol showed no meaningful shifts in the allulose-receiving groups, indicating that while fat loss occurred, cholesterol profiles remained stable.

Investigating Allulose’s Role in Diabetes Management

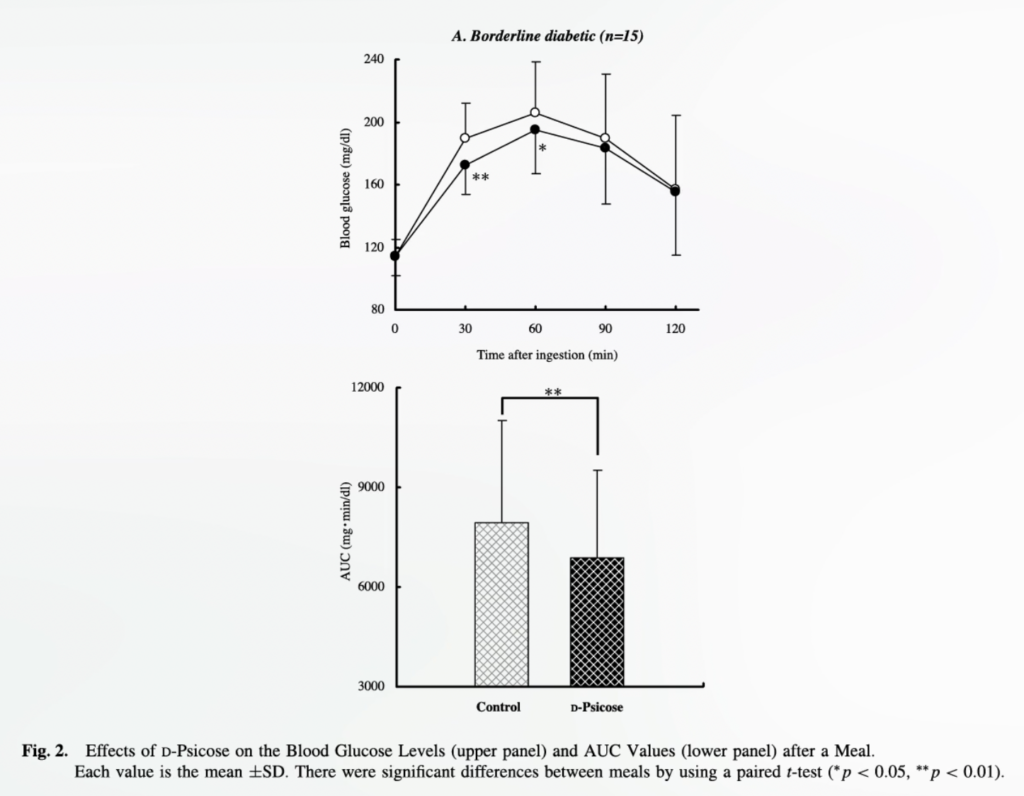

Beyond weight management, attention has turned to allulose’s potential anti-diabetes properties. In a meticulously designed randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover study, participants with borderline diabetes were given a cup of tea sweetened with either 1¼ teaspoons (5 grams) of allulose or a control version without it, alongside a meal. Blood glucose monitoring revealed a substantial drop in sugar levels at both 30 and 60 minutes post-consumption, achieving approximately a 15% reduction relative to the control. However, this benefit faded after the initial hour, suggesting only a short-term moderating effect.

To evaluate prolonged safety and efficacy, the same research team extended their investigation to healthy volunteers. These individuals took slightly more than a teaspoon (5 grams) of allulose three times daily with meals over 12 weeks. No adverse reactions were observed, which is reassuring for safety. Yet, disappointingly, there were no detectable improvements in body weight or fasting blood sugar levels. This mixed picture extends to body fat outcomes across studies and similarly to blood glucose responses, highlighting the need for more consistent evidence.

Further trials have yielded varying results. One examination in healthy subjects found no impact on blood sugar up to two hours after intake. In contrast, a parallel study involving people with diagnosed diabetes reported positive effects. A broader systematic review and meta-analysis synthesizing all controlled feeding experiments concluded that any acute benefits on post-meal blood sugars were only of borderline statistical significance. It remains uncertain if these modest, inconsistent short-term changes could lead to substantial long-term glycemic control. Simply incorporating allulose might not suffice; it may require complementary lifestyle adjustments, such as eliminating processed junk foods, to yield meaningful results.

Assessing Allulose’s Overall Health Impact

Unlike conventional table sugar, allulose demonstrates dental friendliness. It does not serve as a substrate for the oral bacteria responsible for cavities, failing to produce the acids that erode enamel and foster plaque accumulation. Additionally, it avoids elevating blood glucose levels, a key advantage even for those managing diabetes. Classified as a relatively nontoxic sugar, allulose appears benign in metabolic and toxicological evaluations, sparking interest in its broader safety profile.

Determining Safe Intake Limits for Allulose

To pinpoint tolerance thresholds, scientists administered escalating doses of allulose in beverages to healthy adults, aiming to identify the highest single dose suitable for occasional use. Gastrointestinal distress remained absent until reaching 0.4 grams per kilogram of body weight—equivalent to roughly eight teaspoons for an average adult American. At 0.5 grams per kilogram, or about ten teaspoons, severe diarrhea emerged in some participants.

For daily consumption spread across multiple smaller servings, issues like intense nausea, stomach cramps, headaches, or diarrhea surfaced around 17 teaspoons total (1.0 gram per kilogram body weight), varying by individual size. Therefore, prudent guidelines suggest limiting single doses to under eight teaspoons (0.4 grams per kilogram) and capping daily totals at approximately 18 teaspoons (0.9 grams per kilogram) for most U.S. adults to minimize risks.

The Final Word on Allulose as a Sweetener Option

Rare sugars like allulose position themselves as potential healthy substitutes for conventional and artificial sweeteners. Proponents highlight a spectrum of promising effects—from fat reduction and mild glucose modulation to tooth safety—without evident metabolic drawbacks or toxicity in available studies. This positions allulose as arguably the leading candidate among rare sugars. That said, the endorsement carries caveats due to limited high-quality human trials. Experts caution that without robust long-term data, it may be premature to broadly advocate rare sugars for routine dietary inclusion. This hesitancy echoes concerns from past sweetener controversies, such as those surrounding erythritol, underscoring the importance of awaiting more definitive research before fully embracing allulose.