Achieving weight loss through non-surgical methods offers numerous benefits, including the avoidance of risks associated with invasive procedures that alter the gastrointestinal tract.

Understanding the Debate Around Bariatric Surgery

Professionals in the field of bariatric surgery strongly oppose descriptions that liken their procedures to extreme measures like internal jaw wiring or incisions into healthy tissues solely for behavioral modification. Instead, they have rebranded these interventions as “metabolic surgery,” positing that the structural changes to the digestive system trigger shifts in hormone production related to digestion, thereby providing distinct physiological advantages. To substantiate this claim, they highlight the impressive rates of type 2 diabetes remission observed post-procedure.

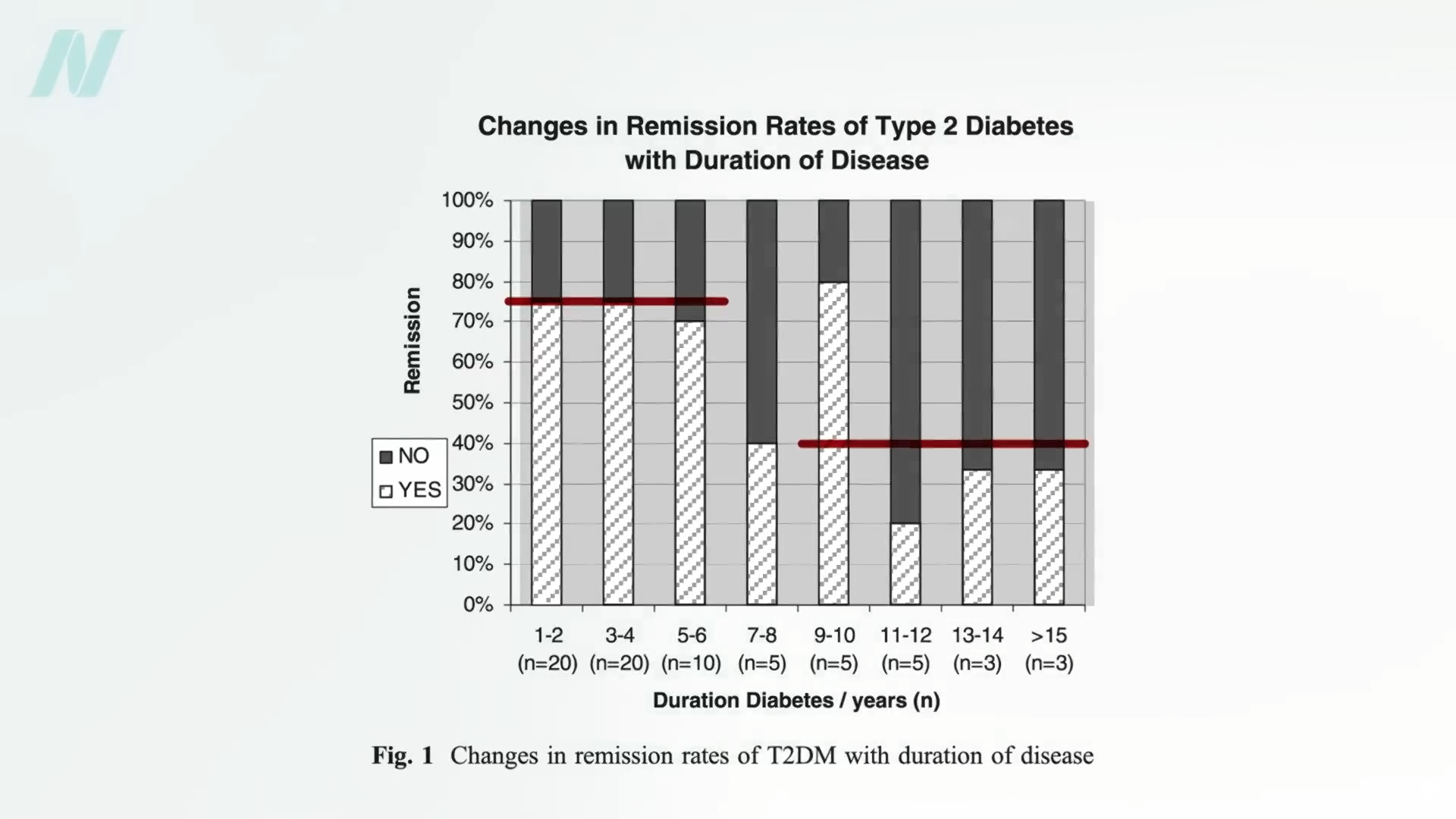

Following bariatric surgery, approximately 50 percent of obese individuals diagnosed with diabetes, and up to 75 percent of those classified as super-obese with the condition, experience remission. This means they maintain normal blood glucose levels while consuming a standard diet, without requiring any diabetes medications. Remarkably, blood sugar normalization can occur within mere days of the operation. Even after 15 years, about 30 percent of these patients remain diabetes-free, in stark contrast to just 7 percent in groups managed without surgery. However, the critical question remains: is this outcome truly attributable to the surgery itself?

Challenges and Risks in Bariatric Procedures

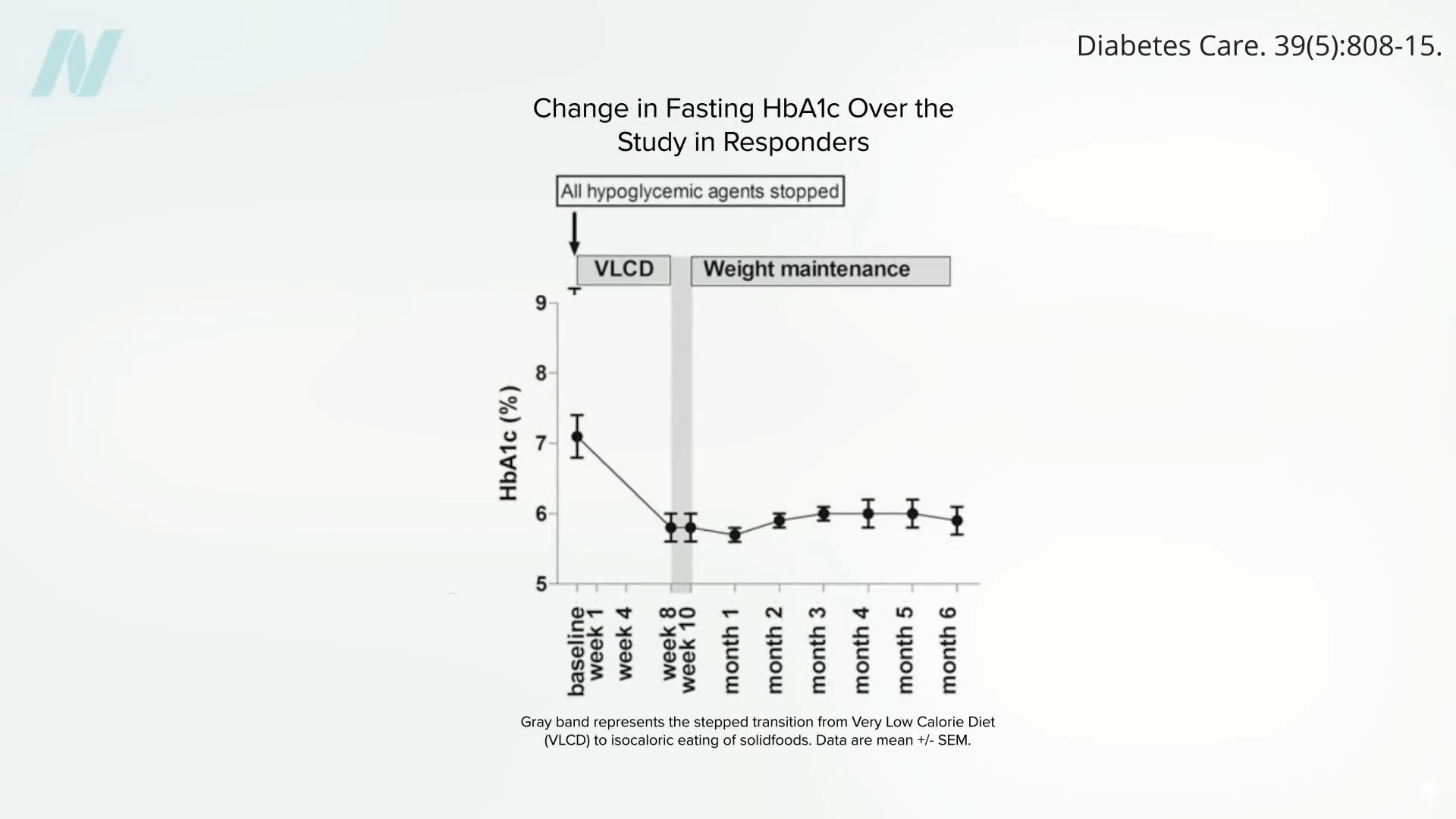

One of the most demanding aspects of performing bariatric surgery involves elevating the liver. In obese patients, livers are often enlarged and laden with fat, heightening the chances of injury and hemorrhage during the process. Such a fatty liver frequently necessitates converting a minimally invasive laparoscopic approach into a more extensive open surgery, resulting in a prominent abdominal scar, elevated risks of infection, other complications, and prolonged recovery periods. Interestingly, shedding just 5 percent of body weight can reduce liver size by 10 percent. This is precisely why patients scheduled for bariatric surgery are routinely prescribed a pre-operative diet. Post-surgery, they are typically transitioned to a severely restricted liquid diet providing very few calories for several weeks. This raises the possibility: could the observed improvements in blood glucose be primarily due to this caloric limitation rather than any purported metabolic effects unique to the surgery? Scientists sought to investigate this hypothesis directly.

Key Study Comparing Diet and Surgery

Researchers at a bariatric surgery center affiliated with the University of Texas recruited patients with type 2 diabetes who were awaiting gastric bypass procedures. These participants agreed to remain hospitalized for 10 days, adhering strictly to the ultra-low-calorie regimen—under 500 calories daily—that mirrors the protocol before and after surgery, but without actually undergoing the operation. Several months later, after regaining their lost weight, the same individuals proceeded with the surgery and replicated the exact same diet schedule. This ingenious design enabled a direct apples-to-apples comparison within the same subjects: identical caloric intake, identical timelines, but one group with surgery and the other without. If the anatomical modifications conferred a special metabolic edge, outcomes should have been superior post-surgery; yet, results indicated otherwise—in fact, certain metrics were inferior with the procedure.

The diet-induced caloric restriction alone yielded comparable enhancements in blood glucose regulation, pancreatic performance, and insulin responsiveness. Moreover, several indicators of diabetes management showed even greater improvement in the absence of surgery. Paradoxically, the surgical intervention appeared to impose a metabolic hindrance.

The Role of Fat Accumulation in Type 2 Diabetes

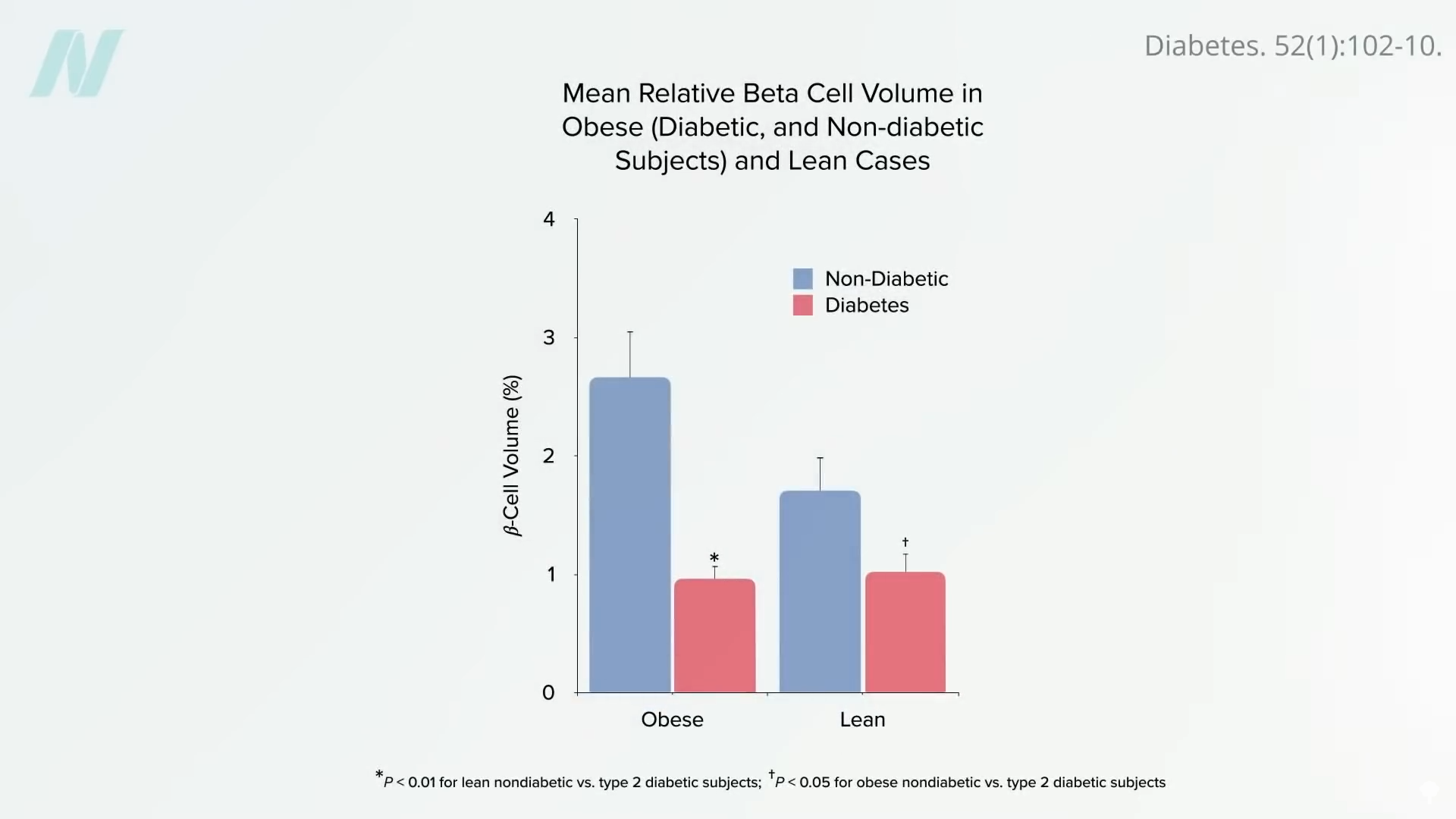

Caloric restriction initiates its benefits by mobilizing fat stores from the liver. The underlying pathology of type 2 diabetes is believed to stem from excess fat accumulation in the liver, which then overflows into the pancreas. Each person possesses a unique “personal fat threshold” beyond which surplus fat cannot be safely stored in typical adipose depots. Once exceeded, lipids deposit in the liver, fostering insulin resistance. The liver may subsequently export some fat via very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) particles, which can infiltrate the pancreas and destroy insulin-producing beta cells. By the point of clinical diagnosis, up to half of these vital cells may already be lost.

Implementing a low-calorie diet can reverse this cascade entirely. A substantial calorie deficit triggers a rapid decline in hepatic fat, restoring liver insulin sensitivity in as little as seven days. Sustaining this deficit further reduces liver fat to levels that normalize pancreatic fat content and function within eight weeks. Dropping below one’s personal fat threshold allows resumption of normal eating patterns while maintaining diabetes control.

Reversibility Depends on Timing and Weight Loss Extent

In summary, type 2 diabetes proves reversible through weight loss, particularly if addressed promptly in its early stages. Individuals who shed more than 30 pounds (approximately 13.6 kilograms) and have endured the disease for under four years achieve non-diabetic blood sugar levels in nearly 90 percent of cases, indicating remission. For those with eight or more years of diabetes, reversibility drops to around 50 percent—still achievable via dietary weight loss alone. Bariatric surgery, enabling even greater weight reduction—often more than double—yields remission in about 75 percent of patients with up to six years of disease duration, falling to roughly 40 percent for longer-standing cases.

Additional Health Benefits of Non-Surgical Weight Loss

Beyond diabetes control, weight reduction without surgical intervention provides further advantages. People with diabetes who lose weight solely through dietary means experience substantial improvements in systemic inflammation markers, such as tumor necrosis factor. In contrast, comparable weight loss via gastric bypass often leads to worsening of these inflammatory indicators.

Impact on Diabetic Complications

A primary motivation for managing diabetes aggressively is preventing associated complications, including blindness or end-stage kidney disease necessitating dialysis. While bariatric surgery can enhance kidney function, it surprisingly fails to halt the onset or advancement of diabetic retinopathy—the leading cause of vision loss in this population. This may arise because surgery influences caloric intake quantity but not dietary quality. A landmark trial in the New England Journal of Medicine randomized thousands of diabetic patients to an intensive lifestyle intervention emphasizing weight loss. Despite rigorous efforts, the study concluded early after a decade, as the intervention did not prolong life or reduce cardiovascular events. The likely explanation: participants adhered to smaller portions of the same atherogenic diet, neglecting qualitative improvements.

Key Takeaways on Diabetes Reversal Strategies

- Extreme caloric restriction, independent of surgery, emerges as the primary driver of diabetes remission. Research demonstrates that such diets alone deliver equivalent or superior gains in glycemic control, insulin sensitivity, and pancreatic health compared to identical regimens paired with bariatric procedures, undermining claims of surgery-specific metabolic superiority.

- Substantial early weight loss reverses type 2 diabetes by depleting ectopic fat from the liver and pancreas. For instance, exceeding 30 pounds of loss restores normoglycemia in nearly 90 percent of cases where diabetes duration is under four years.

- Dietary weight management not only sidesteps surgical perils like hepatic trauma, infections, and scarring but also betters inflammation profiles. Surgical approaches, conversely, may exacerbate inflammation and entail procedural hazards.

- Bariatric surgery ameliorates renal function yet inadequately safeguards against retinopathy, possibly owing to suboptimal post-operative nutrition. Evidence further indicates that weight loss absent dietary quality upgrades fails to mitigate cardiac risks or mortality in diabetics.